by Tracy Bogard | Aug 31, 2022 | Garden2Table, Information

Garden2Table – Can I Freeze Squash? Can I Freeze Squash? From: Kellogg Garden July 2022 Blog Bring a hint of summertime into your meals throughout the entire year by freezing squash and preserving at its peak of freshness. No matter what kind of squash you harvest or...

by scmgadmin | Jul 4, 2022 | Garden2Table, Information

Garden2Table – GARDEN2TABLE June 2022 GARDEN2TABLE 2022 By: Cassandra D’Antonio (SEMG 2012) My husband and I had the opportunity to visit Southern Italy and Sicily the first two weeks in May with fellow SEMGs Sam and John Thompson. Our travels started in Rome, moved...

by scmgadmin | Apr 19, 2022 | Garden2Table, Information

Garden2Table – GARDEN2TABLE April 2022 GARDEN2TABLE 2022 By: Cassandra D’Antonio (SEMG 2012) Foraging for Wild, Native Edible Foods What is Your Gateway to Wild Foods? That was a question Brad Lancaster asked multiples times at the New Mexico Land & Water Summit...

by scmgadmin | Mar 18, 2022 | Garden2Table, Information

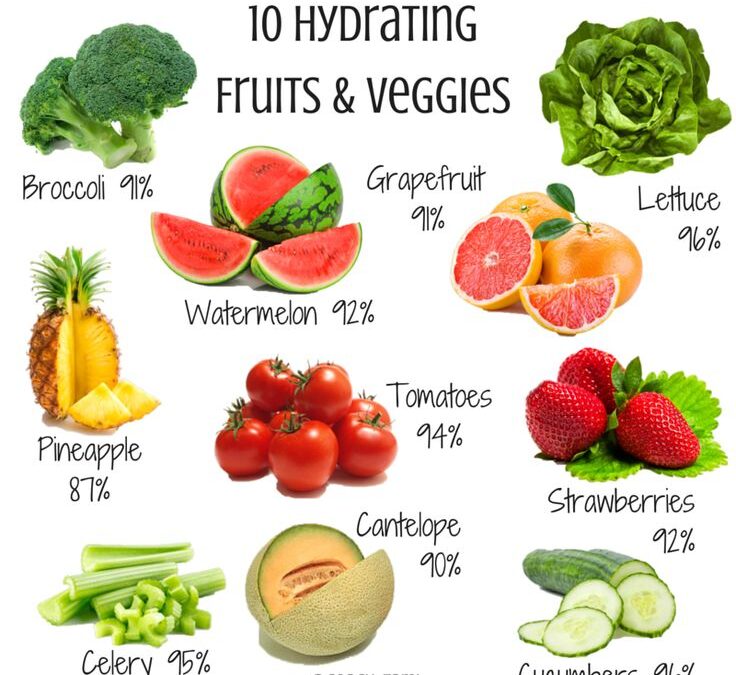

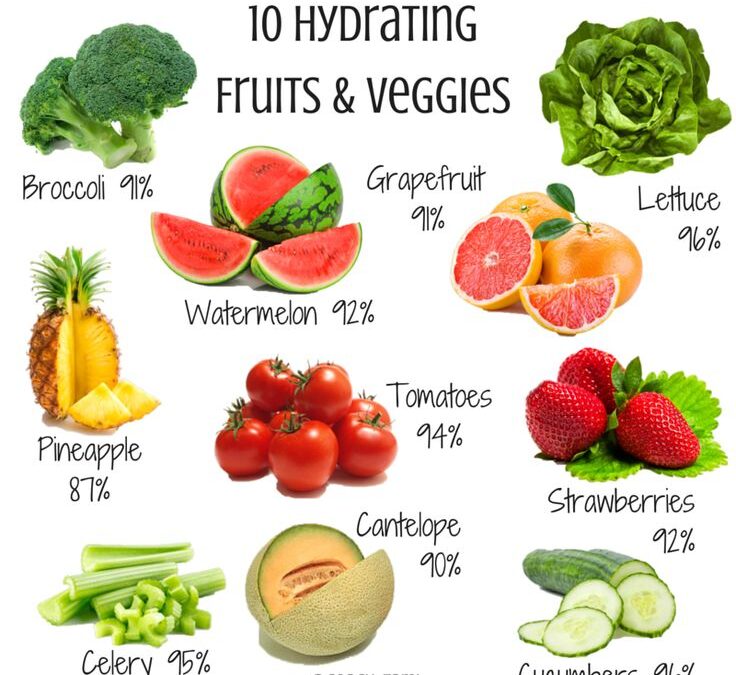

Garden2Table – GARDEN2TABLE March 2022 GARDEN2TABLE 2022 By: Cassandra D’Antonio (SEMG 2012) EAT YOUR WATER, WINTER SALADS & MORE EAT YOUR WATER. How many of you have recently purchased a head of iceberg lettuce? My husband did a few weeks ago when I asked him to...

by scmgadmin | Feb 15, 2022 | Garden2Table, Information

Garden2Table – GARDEN2TABLE February 2022 GARDEN2TABLE 2022 By: Cassandra D’Antonio (SEMG 2012) All About Rutabagas When was the last time you purchased a rutabaga? For me, it was last week after running across more than one food blog or article extolling this...

by scmgadmin | Jan 20, 2022 | Garden2Table, Information

Garden2Table – GARDEN2TABLE January 2022 By Cassandra D’Antonio (2012), Chair A little less than two years ago, the SEMG Garden2Table Outreach Committee was gearing up for a busy year. We had a wonderful group of eager volunteers who had attended training and...